Background

Digital Learning has risen to prominence with many who care deeply about an educated society. Catalyzed by the emergence and widespread fascination with MOOCs, many inside and outside the academy are asking about the implications that Digital Learning has for both residential and non-residential education at universities. The attention around MOOCs, in particular, has been so intense that people are comparing the journey since 2012 to Gartner’s famous “Hype Cycle.” Early on, the focus was on the new, exciting, and potentially transformative impact that digital education can have across the spectrum. But as 2013 gave way to 2014, the hype cycle was clearly headed toward disillusionment as some experiments were abandoned and commentators focused on low completion rates and faculty-voiced concerns regarding (a) the efficacy of MOOCs in comparison, especially, to residential education and (b) control of their intellectual property.

But digital education is more than MOOCs and more than a passing fad. It’s everywhere and it’s growing. The physical classroom is increasingly mediated/enabled/extended by digital technology. We depend on technology to connect with our students, to deliver content to them, and to assess them. Indeed, it is becoming as essential to a residential education as the bricks and mortar in which we dwell.

Thus, our view has always been to focus on the whole of digital education. In 2012, one of us (Brad and his CIC colleagues) wrote a paper “Is This Time Different?” and gave a keynote address to the Australian Innovative Research Universities. In both pieces, the primary theme was the need to focus on the whole of how technical, economic, and social trends might come together for universities as we continue to (1) enhance the great value of a residential education through techniques like Flipped Classrooms; (2) extend learning beyond our campuses with courses and degrees; (3) continue to educate our alumni and others through badges and non-credit short course, and (4) judiciously enable MOOC capabilities for our faculty when they seek to educate the world. They urged near-term experimentation and setting a longer-term strategy that aligned to the opportunities of an increasingly digital university.

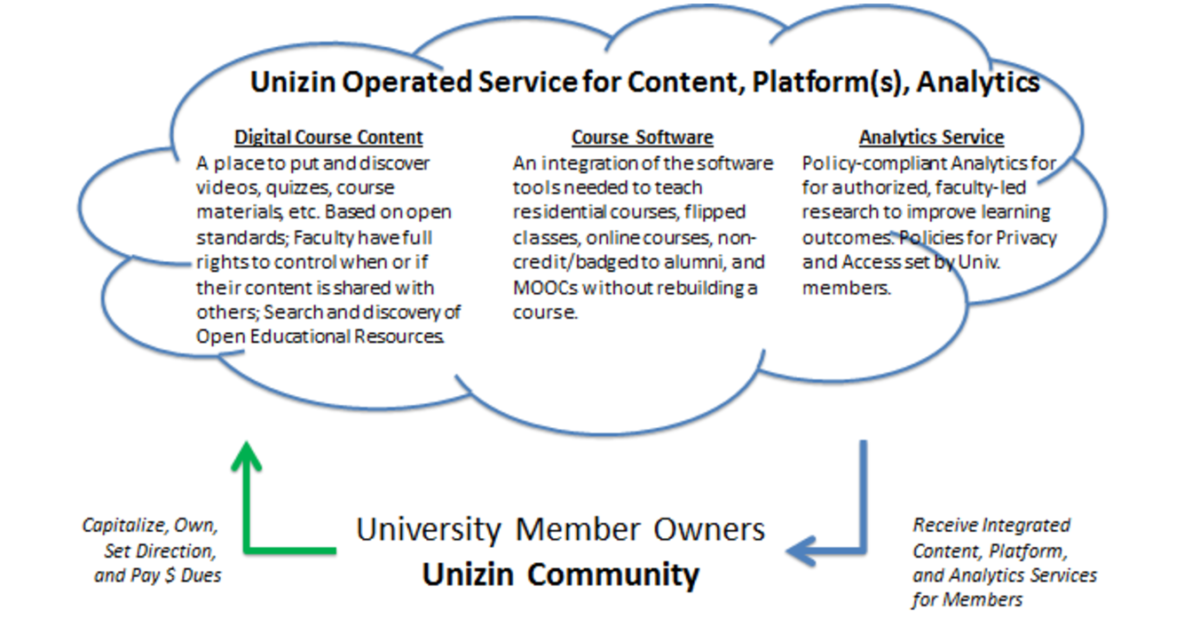

In the months that followed and through countless conversations, it seemed clear that universities and faculty would benefit from a means to control and shape the technologies and services that enable some key parts of Digital Education. These would include the increased digitization of the Content that students/faculty use, the Software Platforms that enable learner interactions via lessons and courses, and the Analytics that may give insight to enhance both Content and Software to improve learning. Data-driven insights from analytics hold great promise to enhance the ways we teach and even inform our curricula.

It also became increasingly clear that isolated, single campus-based approaches to deal with this path to scale would not favor institutions; rather, it would shift control and economic power to entities outside of academia that develop and own technologies and services at scale. These owners would be able to assert the terms for use of content and data on their platforms and would almost certainly add new costs to universities. In that shift of decision rights, long held faculty and student rights regarding control of intellectual property and privacy might no longer be decided in the Academy.

For universities, a path to scale could pose both great opportunity and great risk. What have we learned from the previous 20+ years as essential parts of our education and research enterprise went to scale?

There are many different lessons beyond those expressed here, but two stand out:

- Research universities largely left the publication of journals to others, and that has not worked out well. We now pay an escalating, collective Billions to rent the right to read our own scholarship each year.

- In contrast, in 1996 a group of universities invested their own capital to create Internet2 as a university-owned and operated high performance network. Internet2 did not dig a trench for new fiber optic cable across the nation nor did it create its own routers. Rather, it executed national contracts with leading commercial providers of the day to create the first Abilene network in 1998. Those commercial relationships later evolved to other firms as the network has since been renewed three times and now boasts over 8.8 Terabits of capacity at speeds of 100Gigbits per second speed supporting over 500 members.

The lessons could not be more stark: Universities benefitted immensely when we came together to steer our own path to scale by creating, owning, contracting, governing, and then uniquely using shared infrastructure to serve each university’s mission. Internet2 is our network, and we have decision rights to set policies, business models, terms, and manage costs to best serve higher education.

Unizin is about learning from the past to create a member-owned Internet2 of Digital Education; taking advantage of scale to create shared infrastructure to enable innovation; and giving faculty and students at universities tools to share what they choose to share and to use what they want to use to further education.

Launching Unizin

On 10 June 2014, the first four institutions announced the creation of the Unizin Consortium. The news release and the FAQ have many of the details so they are not repeated here. Unizin has been shaped by many evolving conversations since 2012 to assess the best way to enable long-term success. Future blog posts here will cover some of that territory as Unizin spins up, but in this first post we touch on a few key strategies and choices.

- Unizin is a cloud-scale services operator. With Internet2’s 100Gigabit national network to our campuses and the favorable economics of digital shared services, Unizin will contract for, integrate, and operate shared services for its members. It is not a software project for download and local implementation. It is a shift from premises-based software implementations and local integrations to a cloud-scale, consolidated service off campus. It is not just LMS hosting as the market already has such offerings. Rather, Unizin is an evolving and integrated set of services for Content, Software, and Analytics steered by its members. We envision a professional services staff of around 20+ to integrate and operate the Unizin service.

- Unizin is common infrastructure to support the missions of its university members. It is not a public-facing brand. It will not offer content, courses, or degrees in its own name. By pop culture comparison, Unizin is the “Intel Inside” behind the great brands of its members. We sometimes use the comparison of Unizin to establishing “common gauge rails” that enabled trains to go farther than when each train company had differing gauge rails. As a common infrastructure service, Unizin will make it easier for faculty to work together across institutions when they choose to do so. Common digital learning infrastructure does not differentiate the value of our institutions — it enhances what each of us can do innovatively with it.

- We believe this approach for common infrastructure gives each institution and its faculty the best prerogative to act in ways that serve Strategies of Independence, Dependence, and/or Interdependence for differing parts of their mission and at differing times. See “Strategies for Coping with Curves” in Speeding Up on Curves. Universities are amazing places with many differing needs among schools, departments, and faculty. The opportunities, needs, interests, and timing are not monolithic, and the Unizin service enables each to make use of the infrastructure as suits its current needs.

- After much consideration, Instructure Canvas was chosen to be one of the initial software components for Unizin services. Canvas has established a remarkable record in its use of open IMS Global standards and (mostly) open source software. Many faculty and student groups have developed innovative add-ons through the Canvas open APIs. Through conversations with the Instructure leadership and experiences on many campuses, the founders chose to partner with Instructure to give the Unizin service a very rapid acceleration from day 1. A number of institutions had recently pilot tested Canvas, and others have recently moved with great success.

- The Unizin consortium is designed to be extensible. Just as Internet2 began in its early days with a handful of universities and grew to 34 founders and now has over 251 universities/500 members, we see Unizin as extensible over time. There are many decisions and trade-offs to be made in these early days, and those who are investing the capital to form Unizin will be shaping those decisions. Like Internet2, Unizin will in later years move to a Membership Dues model that provides access to a well-managed shared service. Its fees to its members need to cover all its costs and good operations, but they need not cost more and are not beholden to anyone other than Unizin’s growing roster of members over time.

In the 2012 The Marketecture of Community, we observed:

“Yet colleges and universities face great institutional inertia in adapting to models of intentional interdependence. The structure of U.S. higher education has strongly enabled the habit of “going it alone”—an independence enabled by a plurality of funding sources. Although particular campuses or institutions may feel constrained by state or university rules for multi-campus institutions, the U.S. system remains remarkable for its highly distributed authority of institutional governing boards, executive officers, deans, and shared governance with faculty. Institutions have long had the independent means to choose and fund unique, solo contract solutions for their distinct, geographically separated physical campuses. The collective sum of these costs across the [many colleges and universities] of higher education—a sum that is quite large relative to its modest benefit—looks increasingly peculiar in a digitally connected world of open software and cloud services.

The many virtues of institutional independence are also its many vices. American higher education is a vibrant marketplace of ideas, one that has inarguably yielded numerous benefits over the last fifty-plus years. Protecting and enabling that marketplace for leading research and instruction remains essential; whether higher education can or should sustain such expensive heterogeneity in the many essential services that enable research and education is far more debatable. There is no governance means, other than leadership, to change this expensive trajectory. The responsibility thus falls to leaders—and especially to IT leaders—to inform, influence, engage, debate, and adapt their institutions to an increasingly connected world.”

Unizin is a means to ensure that members of the Academy shape the future in ways that best serve the noble mission that is higher education. It gives universities and their faculties a renewed, action-oriented, collective voice in this vital conversation. It provides a means to reframe and focus our attention on independence, dependence, and intentional interdependence. It is a beginning. Over the coming months and years, we look forward to working with faculty, students, staff, foundations, other universities, and all who treasure the power that education, in its many forms, has to transform lives.

Brad Wheeler, Ph.D.

Founding co-chair, Unizin Consortium

Vice President for IT & CIO

Professor of Information Systems, Kelley School of Business

Indiana University

James L. Hilton, Ph.D.

Founding co-chair, Unizin Consortium

Dean of Libraries and Vice Provost for Digital Education and Innovation

Professor of Information, School of Information

University of Michigan